Dr. Rory Spiegel, from EMNerd, wrote a recent piece in Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine about how our undying love for left ventricular function in shock patients is perhaps overdoing it and the focus should rather be on the venous return. In the 1950’s Guyton et al described the three factors that affect venous return: 1. Right atrial pressure 2. Mean systemic pressure (Pms) 3. Vascular resistance.

The Pms is something that we don’t refer to often in critical care, but as Spiegel argues, should receive more respect than it does. In simple terms, Pms provides the pressure needed to produce a gradient from the venous return into the right atrium for forward flow. Spiegel provides a great analogy using a bathtub and bucket model to explain the physiology, but I’m going to attempt another analogy using a water balloon.

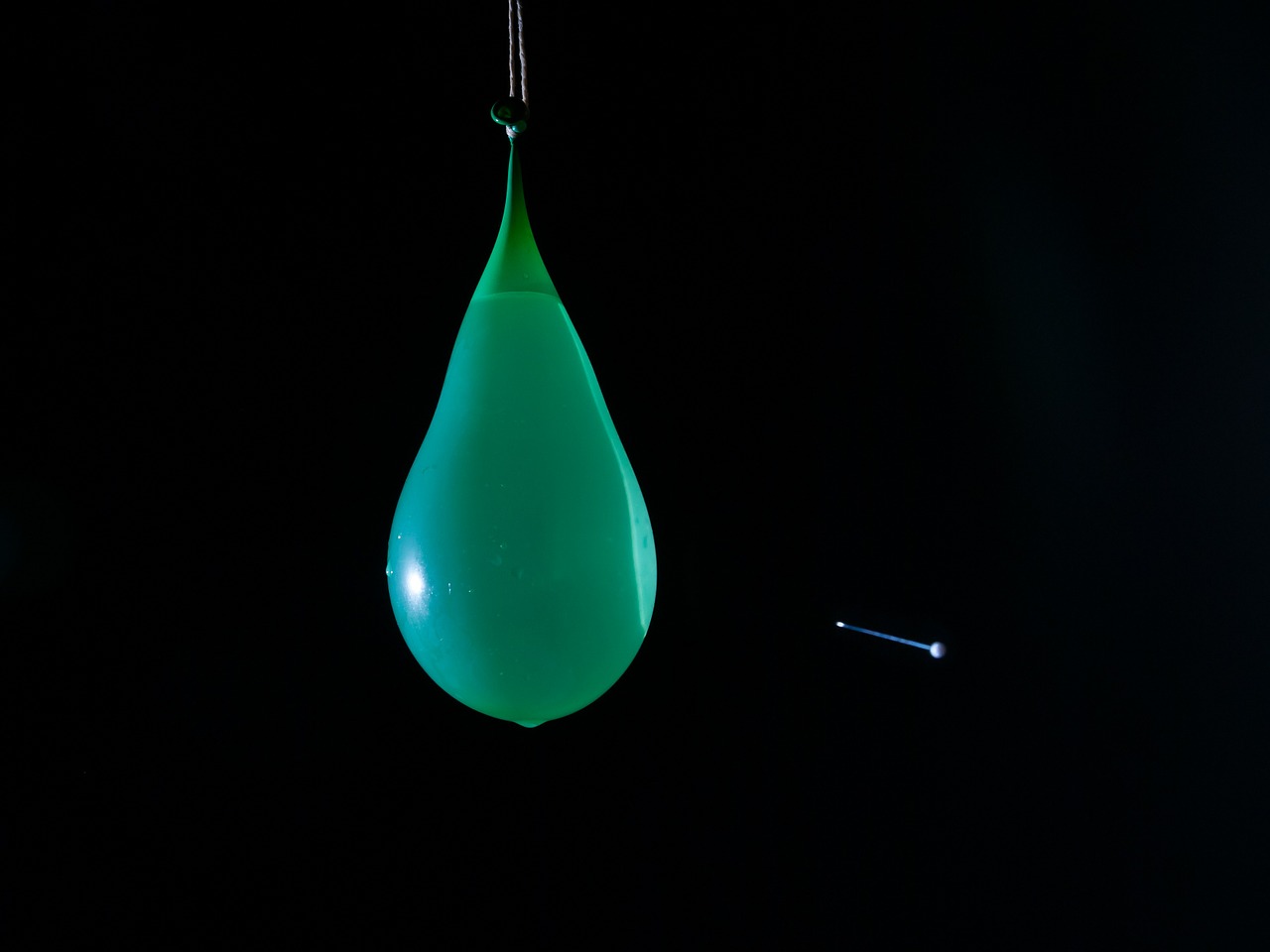

The Pms is composed of the blood within the venous system and the pressure exerted by the vascular bed. In the water balloon analogy, the water within the balloon is the venous blood volume and the physical balloon is the vascular bed. You can imagine, there is a certain amount of water that a water balloon can hold before the balloon starts to expand and enlarge, this is the unstressed volume. As you fill the balloon it grows and the pressure exerted by the walls of the balloon increases, this is called the stressed volume. The stressed volume produces increased Pms and subsequently increases venous return to the right atrium. Now, think of a septic shock patient as an old, ratty balloon that has been inflated too many times and has lost of lot of its elasticity. The amount of water needed in these septic balloons to get to a stressed volume is much more than a normal, healthy, brand-new balloon. Hence why we start with multiple liters of fluid resuscitation in septic shock patients, to try to get them to a stressed volume and improve the venous return. When this doesn’t work, we move onto vasopressors to clamp down on the vascular bed (squeeze the balloon) as another means of increasing Pms and venous return.

With summer around the corner, it’s going to be hard to ignore the similarities between helping your kid prepare for their next water balloon battle and dumping 30cc/kg of fluid into that old ratty, septic water balloon. Check out Spiegel’s piece in Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine for great review of mean systemic pressure and its relation to stressed and unstressed volume here.

Post by: Terrance McGovern DO, MPH (@drtmcg13)