This post first appeared on REBEl EM blog. [Link is here]

Background: Dyspepsia and epigastric pain are common emergency department (ED) complaints affecting one in four adults annually. Twenty percent of these patients have an organic cause while 80% have functional dyspepsia (Moayyedi 2017). Antacids are often a first-line treatment in relieving the discomfort of dyspepsia and epigastric pain (Salisbury 2021). Antacids can be paired with other medications to create the “GI cocktail.” The combination often includes a mixture of antacid, viscous lidocaine, and anticholinergic medication. The belief is that lidocaine will help anesthetize gastric mucosa giving time for the antacid to decrease stomach acidity, while the anticholinergic medications decrease motility and GI secretions. The efficacy of one approach over another, giving an antacid with or without lidocaine or other medications, is unknown.

Paper: Warren J, Cooper B, Jermakoff A, Knott JC. Antacid Monotherapy Is More Effective in Relieving Epigastric Pain Than in Combination With Lidocaine: A Randomized Double-blind Clinical Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(9):905-909. [PMID: 32602148]

Clinical Question: Is antacid monotherapy equivalent to the combination of antacid and lidocaine for treating dyspepsia?

What They Did:

- Australian ED-based single-center, double-blind randomized clinical trial

- Patients enrolled over a 3 month period

- Investigated pain reduction on a visual analog scale (VAS) with antacid monotherapy vs antacid mixed with lidocaine in either liquid or viscous gel form for patients with presumed dyspepsia

- Patients randomized 1:1:1 to receive either antacid alone or one of two different formulations of antacid/lidocaine mixture.

Population:

- Inclusion: Patients > 18 years of age who were prescribed combination antacid plus lidocaine in the emergency department for epigastric pain or dyspepsia.

- Exclusion: Patient refusal to participate, inability to assess pain scale.

Intervention:

- Patients with epigastric pain or dyspepsia were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio into the three arms:

- Arm 1: 10ml of antacid and 10 ml of 2% viscous lidocaine

- Arm 2: 10ml of antacid and 10 ml of 2% lidocaine solution

- Arm 3: 20 ml of antacid

Outcomes:

- Primary: Change in pain score at 30 minutes after medications determined by VAS.

- Secondary:

- Change in pain 60 minutes after medications determined by VAS.

- Palatability (taste, bitterness, texture, and overall acceptability) of the medications.

Results:

- 219 were eligible for enrollment

- 120 patients were approached for the enrollment

- 94 patients enrolled

- 89 patients included for final analysis

- 5 were excluded as pain scores were not obtained

- Subjects were randomly divided into three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio

- 30 patients in viscous lidocaine and antacid arm

- 31 patients in lidocaine solution and antacid arm

- 28 patients in the antacid monotherapy arm

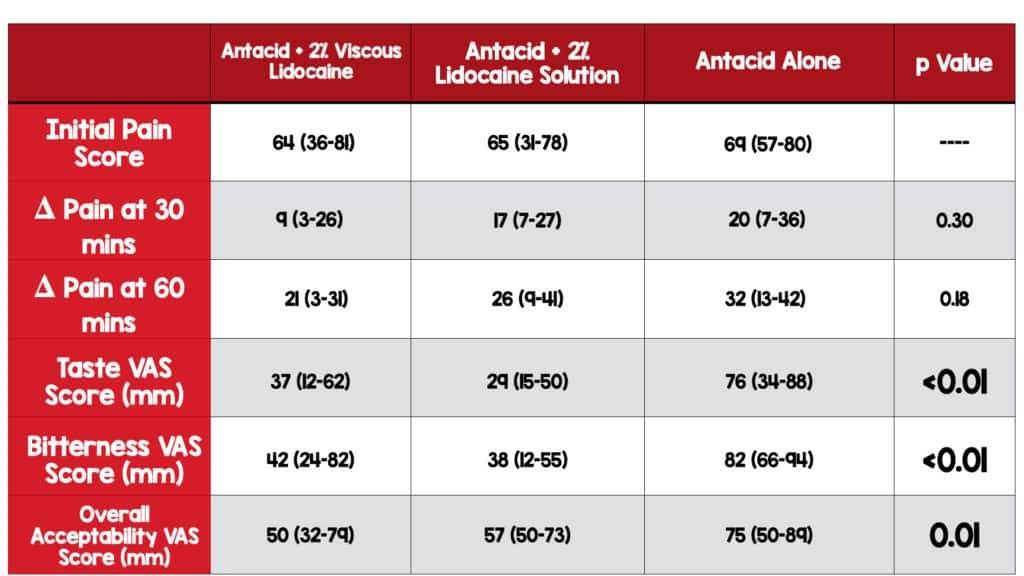

- All groups were found to be equivalent in pain reduction

Primary Outcome: Change in pain 30 minutes

- Mixture of antacid/viscous lidocaine was least effective and antacid monotherapy demonstrated the greatest degree in pain relief

- But no statistically significant difference in pain scores between treatments.

Secondary Outcomes:

- At 60 minutes, all treatment groups experienced additional pain relief

- The change in median pain scores crossed the predetermined minimum clinically important difference and was > 13 mm on VAS for all three arms.

- No statistically significant difference in pain scores between treatments.

- Antacid monotherapy was the most palatable solution

- Statistically significant differences were found in taste, bitterness, and overall acceptability.

Adverse Effects:

- Oral numbness was most common, experienced by the viscous lidocaine (20%) and lidocaine solution (26%) groups

- Dizziness and tiredness reported by the viscous lidocaine and antacid arm (7%)

- Cough, nausea, and dizziness reported by the lidocaine solution and antacid arm (13%)

- Dry mouth reported by one patient (4%) in the antacid monotherapy arm

Strengths:

- Looked at patient satisfaction which is important to consider in compliance with medications.

- Final diagnosis appeared to be balanced between the three groups. Fourteen percent of the patients had a final diagnosis of cardiac pathology, but these were divided evenly between the three groups.

- Outcomes are patient-oriented

- Pragmatic study which is broadly applicable

Limitations:

- Single-center, small study

- Baseline characteristics were unbalanced in some areas (ie PPI use, prior diagnosis of GERD)

- Based on a prediagnostic prescription, 14% of participants had a diagnosis that was cardiac in nature.

- Nurses who administered medications were unblinded which may affect results

- Patients may have known lidocaine leads to numbness and would have known their study arm if they experienced this oral numbness.

- 20 ml of antacid was administered in the antacid arm and only 10 ml in the other two arms. It is unclear how this affected the results.

- It is unclear why lidocaine was prescribed 219 times but only 120 patients were approached for recruitment, raising the suspicion of selection bias.

- Patients were not enrolled consecutively and therefore could have been bias in group assignments

Discussion:

- This is a small single country (Australia) and single-center study which affects generalizability and applicability.

- The predetermined equivalence limit was 13 mm on VAS, and was quite large. The bigger the difference tolerated, the more likely you will conclude equivalence.

- Selection bias was a big problem in this paper.

- Patients were enrolled during daytime hours only and nonconsecutive enrollment can lead to selection bias.

- Patient recruitment depended upon nurses paging investigators when a combination of antacid and lidocaine was prescribed. This recruitment strategy can lead to selection bias.

- Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were prescribed a combination of antacid and lidocaine. There is already some evidence to suggest antacid monotherapy is as effective as combination therapy and perhaps some physicians may have prescribed antacid monotherapy. Those patients would have been missed adding to selection bias.

- 219 patients were eligible for enrollment but only 120 patients were approached. We know nothing about the patients who were missed.

- Unblinding was also a problem.

- Randomization was performed with opaque envelopes which have the potential to be manipulated.

- Nurses were unblinded and knew the study arm allocation as they were preparing the medications.

- Investigators made no attempt to make the mixtures look alike so all parties who saw the medication could have been unblinded.

- Patients who received lidocaine were also unblinded. Lidocaine tastes unmistakably different from antacid monotherapy and causes oral numbness. It’s unclear how that could have affected the study results. Especially since pain is difficult to study and is also fairly subjective.

- Investigators administered the same volume of medication which led to dosing disparities in different arms of the study.

- Patients in the antacid monotherapy arm received twice the dose of antacid as those patients in the lidocaine arms.

- The investigators made no attempt to make the solutions look similar but curiously made certain to administer the same volume of medications.

- How might the study results be affected if the same dose of antacid were given in each arm?

- The study found no statistical difference in pain score on VAS between antacid monotherapy and combination therapy.

- The authors determined antacids alone are a better choice based on the side effect profiles of the medications as well as palatability.

- Patients report less palatability in the lidocaine arms.

- Additional studies could be performed looking at the dose-response curve of antacids to determine the optimal dose.

Authors Conclusions: “20 mL dose of antacid alone is no different in analgesic efficacy than a 20 mL mixture of antacid and lidocaine (viscous or solution). Antacid monotherapy was more palatable and acceptable to patients. A change in practice is therefore recommended to cease adding lidocaine to antacid for management of dyspepsia and epigastric pain in the ED. ”

Clinical Bottom Line:

The authors claim equivalence of antacid monotherapy, but the small sample size, numerous methodological issues, and loss of blinding render this study suboptimal to draw any conclusions. However, we recognize most physicians likely do not feel strongly about either option and therefore, any evidence supporting one treatment may result in practice change.

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- NEJM: The Death of the “GI Cocktail”

- EMRAP:Review of the article discussed above

- EMRAP: The Emergency Department Treatment Of Dyspepsia With Antacids And Oral Lidocaine

- Taming the SRU: Dyspepsia in the ED

References:

- Yadlapati R, Vaezi MF, Vela MF, et al. Management options for patients with GERD and persistent symptoms on proton pump inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(7):980-986. [Link is here]

- Talley NJ, Vakil N; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(10):2324-2337. [Link is here]

- Welling LR, Watson WA. The emergency department treatment of dyspepsia with antacids and oral lidocaine. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(7):785-788. [Link is here]

- Berman DA, Porter RS, Graber M. The GI Cocktail is no more effective than plain liquid antacid: a randomized, double blind clinical trial. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(3):239-244. [Link is here]

- Gallagher EJ, Bijur PE, Latimer C, Silver W. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(4):287-290. [Link is here]

- Weberg R, Berstad A. Symptomatic effect of a low-dose antacid regimen in reflux oesophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(4):401-406. [Link is here]

- Graham DY, Patterson DJ. Double-blind comparison of liquid antacid and placebo in the treatment of symptomatic reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28(6):559-563. [Link is here]

- Vilke GM, Jin A, Davis DP, Chan TC. Prospective randomized study of viscous lidocaine versus benzocaine in a GI cocktail for dyspepsia. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(1):7-9. [Link is here]

- Salisbury BH, Terrell JM. Antacids. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 21, 2021. [Link is here]

- Moayyedi, PM, Lacy, BE, Andrews, CN et al. ACG and CAG Clinical Guideline: Management of Dyspepsia. 2017. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 112(7): 988-1013. [Link is here]

Guest Post By:

Amanda Hall, DO

PGY-1, Emergency Medicine Resident

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Email: [email protected]

Marco Propersi, DO FAAEM

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @marco_propersi

Steven Hochman, MD FACEP

Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @hochmast

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)