This post first appeared on REBEL EM Blog. [Link is here]

Background: Unintentional injuries remain the leading cause of mortality in children. While traumatic brain injuries and thoracic traumas are the top two causes of mortality and morbidity, abdominal traumas are the third most common cause.

Additionally, children are at higher risk for clinically significant intra-abdominal (IAI) injuries as a result of their anatomy in comparison to adults. Therefore, it is critical that emergency clinicians accurately diagnose IAI that requires intervention. Given the sensitivity of abdominal CTs for detecting IAI, emergency clinicians may be susceptible to overuse. Unfortunately, CTs expose patients to high doses of ionizing radiation, placing children at increased risk of developing radiation-induced malignancies. The data now shows that solid organ cancers occur in one out of every 300 to 390 girls and one out of every 670 to 690 boys undergoing abdominal CT.

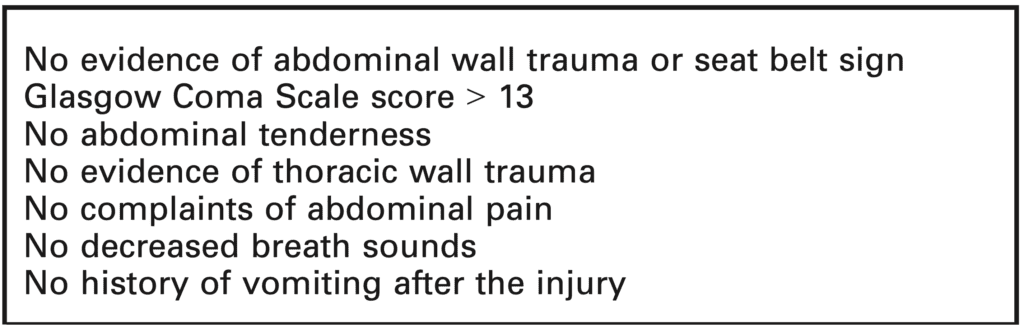

The emergency medicine clinician must balance ruling out deadly diagnoses against the risk of potential radiation-induced malignancy. Prior research derived a clinical decision instrument (CDI) to support emergency clinicians using a one-way rule (Holmes 2013). According to the instrument, clinically significant injury is ruled out if none of the seven criteria are present (Table 1). However, further validation of the CDI is an essential next step

Clinical Question: How does a clinical decision rule compare to physician gestalt in identifying children with IAI following blunt torso trauma requiring acute intervention?

Article: Mahajan P, Kuppermann N, Tunik M, et al. Comparison of clinician suspicion versus a clinical prediction rule in identifying children at risk for IAI after blunt torso trauma. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2015;22(9):1034-1041. doi:10.1111/acem.12739 (PMID: 26302354)

What They Did:

- Planned secondary analysis of data from a prospective observational study

- Internal validation of a clinical decision instrument (CDI) derived in its parent study compared to clinician gestalt

- The parent study was a prospective observational cohort study in children with blunt torso trauma

- Data collected from 20 centers over 2.5 years in diverse patient populations

- Patients were tracked via hospital admission, contacted by phone 7 days after ED visit, mailed a survey, or investigators reviewed medical records, registries, and morgue records to determine if there was an IAI requiring acute intervention or death related to IAI

- Clinicians recorded their suspicions of IAI requiring acute intervention via a data collection form expressed as a percentage

- <1, 1–5, 6–10, 11–50, or >50%

- Clinician suspicion was noted to be “positive” if it was documented as greater than or equal to 1% chance of needing acute intervention

- Clinicians also documented the clinical variables influencing their decisions to obtain CT scans, if applicable

- Emergency medicine doctors determine the clinical probability of IAI requiring acute intervention based on clinical suspicion versus a clinical prediction rule.

Population:

- Inclusion: Children < 18 years old with blunt torso (thorax and abdomen) trauma evaluated in the ED at any of 20 participating PECARN centers from May 2007 to January 2010

- Exclusions:

- Injury occurring > 24 hours before presentation

- Penetrating trauma

- Pre-existing neurologic disorders impeding reliable examination

- Known pregnancy

- Transfer from another hospital with previous abdominal CT or diagnostic peritoneal lavage

- The clinician did not document clinical suspicion of IAI undergoing acute intervention on the data collection form

Outcomes:

- Primary outcome: Comparison of the test characteristics of clinician suspicion with a derived clinical decision instrument to identify children at very low-risk of IAA undergoing acute intervention.

Results:

- 14,882 children were eligible in the parent study

- 12,044 children were ultimately enrolled

- 11,919 included in the secondary analysis

- 761 patients had IAI, 26.7% required acute intervention

- 2,667 patients (22%) had clinician suspicion equal to or greater than 1% of needing acute intervention

- 168 patients (6%) needed acute intervention

- 9,252 patients (78%) had clinician suspicion less than 1% of needing acute intervention

- 35 patients (0.4%) needed acute intervention

- 3,016 (32.6%) of those patients got abdomen and pelvis CTs

Critical Results:

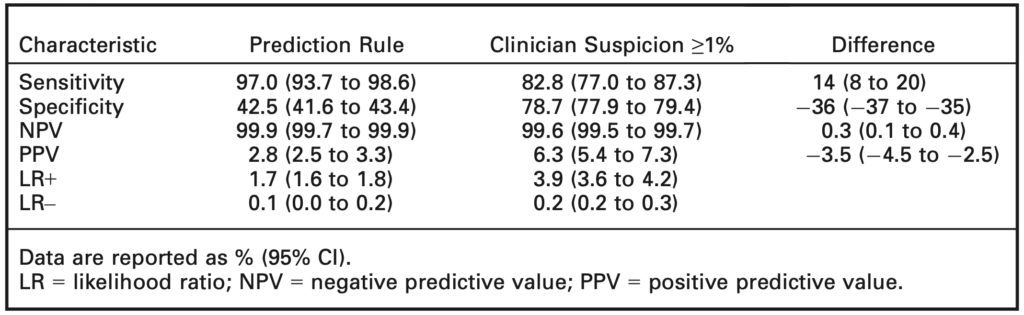

- The prediction rule had a sensitivity of 97% while clinician suspicion had a sensitivity of 82.8%

- Clinician suspicion was much more specific (78.7% versus 42.5%)

- NPV of prediction rule was 99.9%, not much different from clinical suspicion of 99.6%

- One-third of patients deemed to be low risk via clinical suspicion still received abdominal CT scans

Strengths:

- Large, multicenter study with a diverse population

- Consecutive enrollment limiting selection bias

- Prediction rule based on history and physical

- Prevalence of IAI in study is similar to the general population

- Patient-oriented outcome

- Asks a clinically important question with broad implications

- No patients were lost to follow up

Limitations:

- Not everyone in the study received a CT scan

- Clinically silent injuries may have been missed

- The study sites used a large number of tertiary care pediatric EDs where rates of CT use may be lower than those in non-children’s hospitals or general EDs

- Clinician suspicion did not correlate with CT ordering practices

- Composite outcome ranging from death to IV fluids for 48 hours for children with pancreatic or gastrointestinal injuries where all pieces of the composite are not clinically equal in importance

Discussion:

- While the study sought to evaluate the reasons for CT use when clinical suspicion was <1%, in practice clinicians may use other diagnostic modalities:

- Labs (UA for hematuria and CMP for elevation in ALT/AST)

- Serial abdominal exams and vital signs

- Bedside Ultrasound

- Observation

- The CDI is more sensitive (97.0% versus 82.8%), but less specific than clinician suspicion (42.5% versus 78.7%)

- The sensitivity of the CDI is 97% with a 95% confidence interval between 93.7-98.6%; some physicians may be uncomfortable with the possibility of missing up to 6.3% clinically significant IAI

- Nevertheless, CDIs are best when used to rule something out, so maximizing sensitivity at the expense of specificity is clinically useful

- Even though clinician suspicion was found to be more specific, one-third of children who were documented to have a <1% chance of clinically significant IAI still received a CT scan

- In the parent study, 25% of patients considered very low risk by the prediction rule underwent an abdominal CT scan

- This makes up 23% of all abdominal CT scans obtained. This suggests that using the CDI can achieve up to a 25% reduction in unnecessary abdominal CT scans

- Thirty-five patients with a documented clinical suspicion of <1% had clinically significant IAI; 3 (9%) of these patients were deemed very low risk by the CDI

- This brings up the question: should the CDI be used when clinician suspicion for clinically significant IAI is low, or as a screening tool to better tease out who is low risk?

- Despite its lower specificity, the rule would have helped clinicians identify 91% of these injuries

- All children were grouped together no matter the age

- Abdominal exams in younger children are less reliable, so it is important to stratify children by age group

- This would help us identify if rates of CT scans were equal across the board, or if there were certain age ranges that underwent more CTs

- Young age was cited as the 4th most common reason why clinicians ordered CT scans

- While not everyone had an abdominal CT scan, this overall does not affect the outcomes of the study as clinically silent abdominal injuries are not of clinical importance

- The risk of solid organ malignancy far outweighs the knowledge of a clinically silent abdominal injury

- The study uses a composite outcome ranging from death to IV fluids for 48 hours for children with pancreatic or gastrointestinal injuries

- Using a composite outcome in a clinical decision rule is important so that it can capture as many patients with clinically significant injuries as possible

- However, composite outcomes may also leave the trial vulnerable to bias

- Death isn’t the same as IV fluids for 48 hours

- Therapeutic intervention at laparotomy isn’t clearly defined

- The researchers, did, however, break down each outcome individually so we can see how much each outcome drives the overall results

- This is a one-way rule.

- If all criteria are absent, then we may safely avoid imaging.

- However, if any criteria are present, it does not necessitate imaging.

- Instead, it means we can not use the instrument. We may still rely on clinical gestalt or another mechanism if desired.

- Clinician suspicion did not correlate with CT ordering practices.

- Even though clinicians had low suspicion, many scanned anyway.

- While clinical gestalt performs well, the CDI may actually reduce imaging utilization by having something the clinician can document

- Additional studies should focus on clinical impact and resource utilization reduction.

- External validation was done in 2018 via a retrospective review of a trauma registry at a single center (PMID: 30502218)

- Retrospective review of a single-center is a relatively low level of evidence for clinical decision instruments. So a more robust external validation would be required before widespread adoption.

Author Conclusion: “A clinical prediction rule had a significantly higher sensitivity than clinician suspicion for identifying intra-abdominal injury undergoing acute intervention, but a lower specificity. The higher specificity of clinician suspicion, however, did not translate into clinical practice as clinicians frequently obtained abdominal computed tomography scans in patients they considered to be very low risk. If validated, this clinical prediction rule can assist in clinical decision-making around computed tomography use after blunt abdominal trauma in children by limiting computed tomography scan use in low-risk patients.”

Clinical Bottom Line:

This clinical decision rule shows great promise to reduce unnecessary and potentially malignancy-inducing CT scans in children at low risk for IAI following blunt abdominal trauma. In addition, due to its high sensitivity, it can safely rule out IAI needing acute intervention without abdominal CT scans. However, before widespread adoption, the CDI needs to be externally validated in large diverse, prospective multicenter studies.

References:

- Holmes JF, Lillis K, Monroe D, et al. Identifying children at very low risk of clinically important blunt abdominal injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):107-116.e2. [PMID: 23375510]

- Springer E, Frazier SB, Arnold DH, Vukovic AA. External Validation of a clinical prediction rule for very low risk pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med 2018. [PMID: 30502218]

- Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:700–7. [PMID: 23754213]

- Haasbroek C, Wallin D. Pem pearls: To scan or not to scan? CT abdomen in children with blunt torso trauma. ALiEM. https://www.aliem.com/pem-pearls-blunt-torso-trauma. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed December 15, 2021.

- Fox SM. Low risk for intra abdominal trauma. Pediatric EM Morsels. https://pedemmorsels.com/low-risk-intra-abdominal-trauma/. Published January 21, 2015. Accessed December 15, 2021.

Guest Post By:

Sarah Aly, DO

PGY-2, Emergency Medicine Resident

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @alyalyoxenfree_

Eric Steinberg, DO, MEHP

Program Director, Emergency Medicine Residency

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter:@estein54

Marco Propersi, DO FAAEM

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @marco_propersi

Steven Hochman, MD FACEP

Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @hochmast

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)