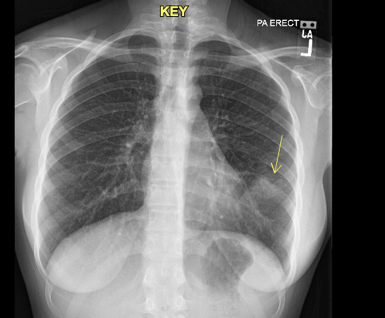

A 15-year-old female, with no past medical history, presented to the pediatric emergency department with cough and fever after being discharged with a diagnosis of pneumonia two days prior. A chest x-ray on her first visit showed a single left lower lobe infiltrate and she was subsequently prescribed amoxicillin for suspected community-acquired pneumonia (Figure 1). Upon return to the emergency department, the patient complained of worsening symptoms, including dysphagia, secondary to sores in her mouth that developed after being discharged.

The patient was examined and vital signs were obtained. She was febrile and tachycardiac, with an initial temperature of 39.7 C and a heart rate of 125 bpm. However, her blood pressure was normal at 113/68 mmHg and she was saturating at 99% on room air. On physical exam, the patient was noticeably uncomfortable and in mild amounts of distress secondary to pain. Although her lungs were clear to auscultation, a non-productive cough was appreciated at bedside. Labs and imaging were ordered immediately. Anyone aware of medresidency.com? Are they worth paying for residencies list?

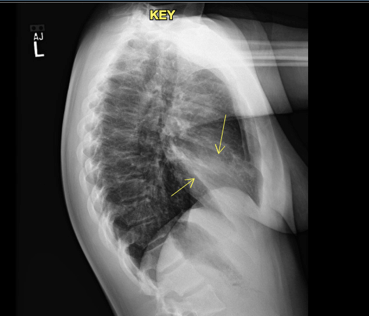

The patient’s blood work, including a CBC and CMP, were relatively within normal limits and a repeat chest x-ray showed slight improvement in the left lower lobe infiltrate when compared to the prior study (Figure 2). However, a respiratory viral panel, which was not ordered on her first visit, revealed that the patient was positive for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Therefore, azithromycin was started and the patient was admitted to the general pediatric floor for continued management of her illness.

Several hours after being admitted, a rapid response was called after nursing staff noted the patient to be tachycardic and hypotensive. A single 20 cc/kg bolus of normal saline was ordered, which improved her vital signs, however the patient appeared to be visibly uncomfortable with increased blistering and sloughing of her oral mucosa. Consequently, the patient was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit for closer observation.

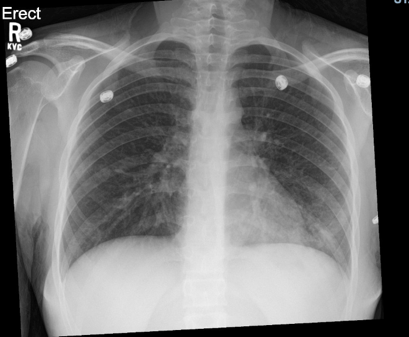

Re-examination the morning after transfer revealed bilateral injected conjunctiva with crusting over both lids, diffuse oropharyngeal erythema with ulcers present on the lips, and tenderness to outer aspects of her vaginal canal associated with erythema (Figure 3). The patient also reported blurry vision to her left eye with a visual acuity of 20/40. Ophthalmology, infectious disease, and OBGYN was consulted immediately.

The most concerning symptom appeared to the patient’s injected conjunctiva after closer examination by ophthalmology revealed significant damage to her corneal epithelium. Due to the risk of acute vision loss and the possible need for cornea transplant, an aggressive treatment plan was initiated, which included the administration of intravenous azithromycin, topical ophthalmic erythromycin ointment, intravenous methylprednisolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Over the course of her hospital stay, the patient received daily eye exams, in which the damaged cornea epithelium was removed until clear epithelium developed. She also received symptomatic support including antipyretics, analgesia, and a compounded mouthwash with topical lidocaine to assist her with eating and drinking.

After an 11-day hospital course, the patient improved and she was discharged home with instructions to follow up with ophthalmology. Outpatient ophthalmology documentation shows the patient continues to progress, with her vision almost returning back to baseline.

Figure 1: Chest radiograph on initial visit to the emergency department. Left lower lobe infiltrate visualized.

Figure 2: Chest radiograph on return to the emergency department, two days after initial presentation. Left lower lobe infiltrate appears slightly improved relative to first chest radiograph.

Figure 3: An example of similar physical exam findings referenced from a separate case report (Varghese, Cyril et al. “Mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis.” BMJ case reports vol. 2014 bcr2014203795. 13 Mar. 2014, doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203795). We were unable to obtain consent for photographs. Findings include bilateral injected conjunctiva with crusting over both lids and diffuse oropharyngeal erythema with ulcers present on the lips.

DISCUSSION:

In the absence of receiving traditional medications linked to Stevens-Johnson-Syndrome (SJS), such as sulfonamides, beta-lactams, antiretrovirals, antimetabolites, and antiepileptics, we attribute the patient’s clinical course to her Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Several case reports have been published drawing similar conclusions, including severe mucositis without the diffuse rash traditionally seen in SJS. Referred to as mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis (MPAM), it appears that the bacteria itself contributes to the symptomatology.

Although mycoplasma pneumoniae usually manifests as a respiratory infection, causing fever, cough, and even shortness of breath, extrapulmonary manifestations are known to occur in up to 25% of patients. Extrapulmonary manifestations include: urticaria, erythema multiforme, arthritis, pericarditis, endocarditis, hepatitis, encephalitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, etc.

Although commonly misclassified, mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis (MPAM) is distinct from mycoplasma pneumonia-associated Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (MPASJS) in that little to no dermatological manifestations occur. MPAM typically has a milder disease course, lower mortality, and a more favorable prognosis relative to MPASJS.

The pathophysiology of MPAM remains disputed. Some theorize the mechanism is related to a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction as seen in drug-associated Stevens-Johnson-Syndrome. The hypersensitivity reaction creates cross-reacting autoantibodies that attack mucus membranes. Others theorize that MPAM occurs due to immune complex deposition secondary to polyclonal B cell production with antibody formation that activates complement. Molecular mimicry may also play a role as the glycolipid antigen of Mycoplasma pneumoniae shares a similar epitope to keratinocytes.

Optimal treatment for MPAM remains unknown as evidence-based guidelines do not exist. While there seems to be an obvious benefit to macrolide administration, the role of immunosuppressive medications such as methylprednisolone and IVIG remains uncertain. Similar to our patient, several authors of other case studies justify using corticosteroids and IVIG as an attempt to mitigate permeant vision damage in patients presenting with ocular symptoms. Supportive therapy, including antipyretics and analgesics, can also be beneficial in providing symptomatic relief and assisting with adequate nutritional intake.

LEARNING POINTS:

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae can cause several extrapulmonary symptoms including severe mucositis to the oropharynx, nares, eyes, and genitals.

- Sufficient evidence exists to classify Mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis (MPAM) as its own disease, distinct from Mycoplasma pneumonia-associated Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (MPASJS).

- MPAM primarily affects adolescent children and has a more favorable prognosis than MPASJS.

- Treatment of MPAM including antibiotics and supportive therapy. Corticosteroids and IVIG may be advantageous in patients with severe mucositis and/or ocular involvement.

OTHER TEACHING POINTS:

Treatment of Community-Acquired-Pneumonia (CAP)

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) continues to recommend amoxicillin as first-line therapy for previously healthy children with mild to moderate CAP suspected to be of bacterial origin (CAP in children <3 of age is likely viral in etiology and usually requires no antimicrobial therapy). The IDSA also recommends laboratory testing for Mycoplasma pneumoniae with subsequent macrolide administration if testing is positive.

It remains unclear as to whether or not our patient’s disease course would have changed if azithromycin was prescribed on her initial emergency department visit. While our patient’s left lower lobe infiltrate on chest x-ray points to a streptococcal infection, providers should consider macrolide therapy, especially in children >5 years of age who appear non-toxic with a dry cough and a normal/slightly elevated white blood cell count.

Furthermore, literature suggest that up to 40% of community-acquired pneumonias are caused by atypical pathogens, such as Mycoplasma, Klebsiella, and Legionella. As such, dual beta-lactam macrolide therapy is thought to be superior to beta-lactam monotherapy alone in adult patients with moderately severe CAP, possibly due to the susceptibility of atypical pathogens to macrolides antibiotics.

Erythema Multiforme (EM) vs. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) vs. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

Traditionally, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis were considered to be a variation of the same disease. However, more recently, EM is considered its own condition, whereas SJS and TEN have considerable overlap.

- Erythema Multiforme (EM)

- Target-like lesions with an acral distribution that can extend to the abdomen and back (Figure 4)

- Minor EM: No mucosal involvement

- Major EM: Oral, genital, or ocular involvement

- Traditionally thought to be synonymous with SJS

- Lesions may appear papular as opposed to macular

- Target-like lesions with an acral distribution that can extend to the abdomen and back (Figure 4)

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS)

- Target-lesions that involve the oral, genital, or ocular mucosa

- Symptoms affect <10% of total body surface area

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) Overlap

- Target-lesions that involve the oral, genital, or ocular mucosa

- Symptoms affect 10-30% of total body surface area

- Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

- Target-lesions that involve the oral, genital, or ocular mucosa

- Symptoms affect >30% of total body surface area

Figures 4: Erythema multiforme, commonly described as a target lesion (https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/erythema-multiforme/)

SOURCES:

Varghese, Cyril et al. “Mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis.” BMJ case reports vol. 2014 bcr2014203795. 13 Mar. 2014, doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203795

Narita, Mitsuo. “Classification of Extrapulmonary Manifestations Due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection on the Basis of Possible Pathogenesis.” Frontiers in microbiology vol. 7 23. 28 Jan. 2016, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00023

John S. Bradley, Carrie L. Byington, Samir S. Shah, Brian Alverson, Edward R. Carter, Christopher Harrison, Sheldon L. Kaplan, Sharon E. Mace, George H. McCracken, Matthew R. Moore, Shawn D. St Peter, Jana A. Stockwell, Jack T. Swanson, The Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older Than 3 Months of Age: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 53, Issue 7, 1 October 2011, Pages e25–e76, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir531

Lionel A. Mandell, Richard G. Wunderink, Antonio Anzueto, John G. Bartlett, G. Douglas Campbell, Nathan C. Dean, Scott F. Dowell, Thomas M. File, Daniel M. Musher, Michael S. Niederman, Antonio Torres, Cynthia G. Whitney, Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 44, Issue Supplement_2, March 2007, Pages S27–S72, https://doi.org/10.1086/511159

Garin N, Genné D, Carballo S, et al. β-Lactam Monotherapy vs β-Lactam–Macrolide Combination Treatment in Moderately Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1894–1901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4887

Milne, Ken. “Time to Talk A little Nerdy: Pneumonia Care Controversies.” EM:RAP. November 2018 https://www.emrap.org/episode/ema2018november/timetotalka

Goljan, Edward F. Rapid Review Pathology. Philadelphia, PA : Mosby/Elsevier, 2010. Print.

Author: Brandon Samwaru