This post first appeared in REBEL EM Blog [Link is here}

Background: Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 have an increased risk of thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). In addition, COVID-19 patients with increased coagulation parameters such as D-dimer, fibrin degradation products, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality. (Al-Samkari 2020)

Several RCTs have investigated the benefit of anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 in various clinical settings. The INSPIRATION Trial investigated outcomes with an intermediate vs. standard prophylactic dose of anticoagulation in ICU patients. A multiplatform trial [Link is Here] and HEP-COVID Trial [Link is here] investigated therapeutic anticoagulation in critically ill and non-critically ill hospitalized patients. The ACTIV-4B Trial [Link is here] investigated anticoagulation in symptomatic COVID-19 patients who did not require hospitalization.

Currently, there is some evidence in support of therapeutic anticoagulation in non-critically ill hospitalized patients. However, there is no evidence to support the use of full dose anticoagulation in either the ICU or outpatient setting(Conors 2021) (Spyropoulos 2021).

Article: Ramacciotti E, Barile Agati L, Calderaro D, et al. Rivaroxaban versus no anticoagulation for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis after hospitalisation for COVID-19 (MICHELLE): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10319):50-59. PMID: 34921756

Clinical Question:

Does extended thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization due to COVID-19 decrease rates of venous and arterial thromboembolism events in high-risk patients?

What They Did:

- Pragmatic, open-label, multi-center, randomized control trial with blinded adjudication.

- Patients enrolled from 14 hospitals in Brazil.

- Participants screened between Oct 8, 2020, and June 29, 2021

- Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 10 mg rivaroxaban per day or no anticoagulation (without placebo) for 35 days.

- Patients were followed up either by telephone call or in-person assessment on day 7 and then again by an in-person assessment on day 35. At that time, bilateral venous doppler ultrasounds and CT pulmonary angiogram were performed.

Population:

- Inclusion Criteria:

- Patients >18 years old, hospitalized due to COVID-19 for a minimum of 3 days.

- Received prophylactic anticoagulation during inpatient treatment (40 mg enoxaparin daily, 5000 IU unfractionated heparin 2-3 times daily, or 2.5 mg fondaparinux once daily)

- Increased risk of venous thromboembolism at hospital discharge is defined as:

- IMPROVE score of 2-3 with D-dimer > 500 ng/mL

- IMPROVE score of 4 or more regardless of D-dimer value

- IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism) Score (Spyropoulos 2011)determined by the presence of:

- Previous VTE (+3)

- History of thrombophilia (+2)

- Lower limb paralysis (+2)

- Current active cancer (+2)

- Immobilization for seven days or greater (+1)

- ICU/CCU admission (+1)

- Age >60 (+1)

- Exclusion Criteria:

- Absent, negative, or inconclusive RT-PCR for COVID-19

- IMPROVE score <4 and normal D-dimer

- Other diagnoses requiring the use of anticoagulation

- Hemorrhage within three months of randomization or during their hospitalization

- Major surgery or trauma within four weeks of randomization

- Any major surgery or procedure planned during the study period

- INR >1.5 without a known elevated INR, history of bleeding diathesis, or coagulopathy

- History of any intracranial hemorrhage in the past, intracranial neoplasia, or arteriovenous malformation

- Active GI ulcer or arteriovenous malformation of the GI tract

- Severe renal failure (CrCl <30 mL/min)

- Liver failure that has caused impaired coagulopathy or other moderate to severe impairment

- Platelet count < 50 x 109 cells/l

- Active cancer

- HIV infection

- Above-knee amputation (bilateral or unilateral)

- Allergy or intolerance to rivaroxaban

Intervention:

- 10 mg/day Rivaroxaban for 35 days post hospitalization

Control:

- No intervention

Outcomes:

Primary Outcome: Composite endpoint at day 35 of:

- Symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE)

- VTE related death

- Asymptomatic VTE detected via venous duplex of bilateral lower extremities or CT pulmonary angiogram.

- Symptomatic arterial thromboembolism (ATE) including myocardial infarction, non-hemorrhagic stroke, or major adverse limb event

- Cardiovascular death

Secondary Outcome:

- Combination of symptomatic or fatal VTE

- Composite of symptomatic VTE or all-cause mortality

- Composite of symptomatic VTE, MI, non-hemorrhagic stroke, or cardiovascular death

Primary/Secondary Safety Outcomes:

- Major bleeding

- Clinically relevant non-major bleeding events (defined by the ISTH criteria)

- Other bleeding events (not defined by the ISTH criteria)

Results:

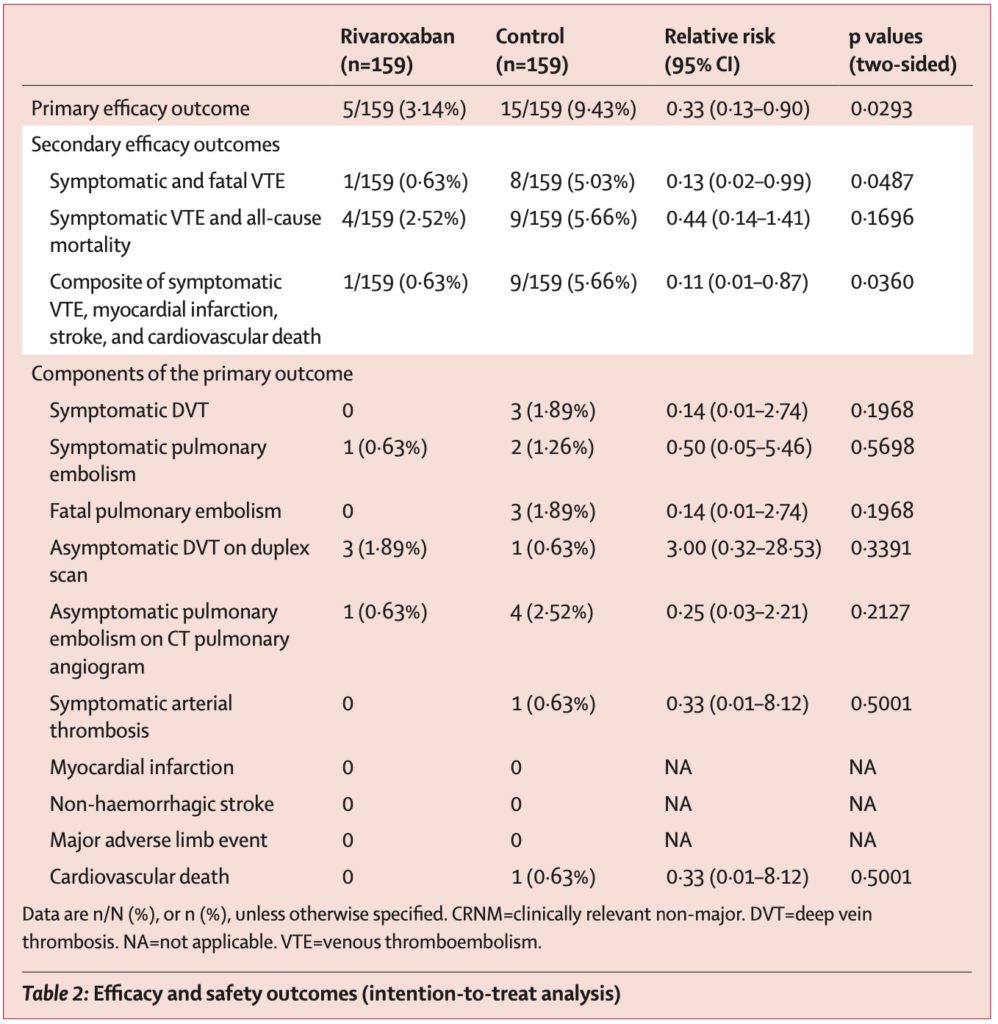

- 997 patients were initially screened for the study.

- 320 patients were eligible for inclusion and were randomized to receive rivaroxaban or no intervention.

- After two patients withdrew consent, 159 patients in each group were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

- Two patients in the rivaroxaban group did not start treatment (one patient joined a different study, another patient required extended hospitalization and, therefore, longer parenteral anticoagulation).

- The Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) is 6.29%, and thus 16 patients would need to be treated to prevent one primary outcome event (Number Needed to Treat = 16).

Strengths:

- This study asks an essential patient-centered question regarding thromboembolic events in high-risk patients with COVID-19.

- Inclusion of multiple hospital centers and patients 18 years and older increases generalizability.

- Blinded adjudication of the outcomes helps to limit bias.

- Baseline characteristics of patients were balanced.

Limitations:

- This trial was an open-label and non-placebo study; therefore, both patients and the trial investigators knew the group assignments, which introduced bias.

- Although this was a multicenter study, all centers were located in Brazil, limiting generalizability.

- The extensive exclusion criteria limit generalizability.

- D-Dimer was used to determine patients’ risk for VTE. However, the D-Dimer could be measured at any point during the patient’s hospitalization.

- On follow-up day 7, patients could be evaluated in person or by telephone. It would be challenging to diagnose asymptomatic VTE in those patients assessed via telephone, which is one component of the primary outcome.

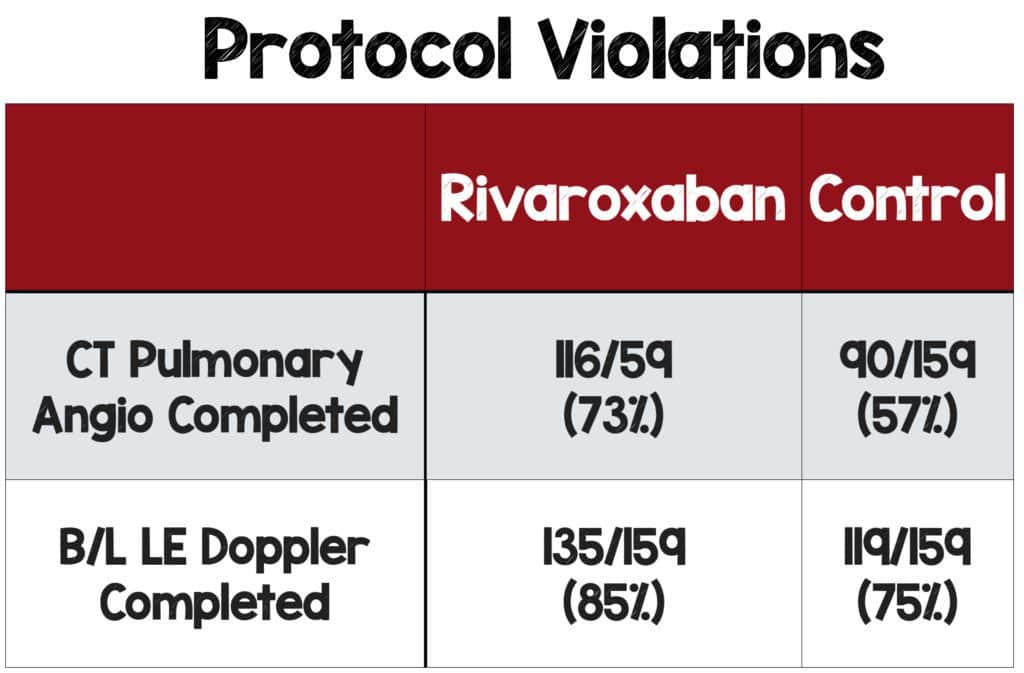

- Not all patients had an ultrasound of the lower extremity or CT angio of the chest as required in the protocol, which can also introduce bias.

- Subsegmental PE was included in the primary composite outcome along with proximal PE. Many studies on VTE exclude subsegmental PE because treatment with anticoagulation is controversial.

- The primary outcome was a composite of multiple endpoints, which do not all hold equal clinical significance.

Discussion:

- Study Design:

- Open-label trials always pose some concern for the potential of bias when making treatment decisions and interpreting results. In this particular study, they used blinded adjudication so that outcomes were assessed by clinicians that were not involved in the study, which helps to limit bias.

- Appropriate and consistent evaluation of patients for the primary outcome is essential. To increase the certainty a patient does not have an asymptomatic DVT (a component of the primary outcome), the patient should have a physical exam.

- D-Dimer:

- D-Dimer is one component of the IMPROVE score, used to determine patients’ risk for VTE.

- However, the timing of the lab value was not standardized and could be measured at any point during hospitalization, as long as it was before discharge.

- It is unknown if patients with an elevated D-Dimer at discharge have the same VTE risk as patients who had an elevated D-Dimer earlier in their hospitalization.

- Composite Outcomes:

- Composite outcomes can be used to decrease the sample size required to demonstrate statistical significance.

- Of note, symptomatic atrial thromboembolism and cardiovascular death were added to the composite outcome after the trial was registered with clinicaltrial.gov.

- The composite endpoint included multiple components ranging from an asymptomatic DVT to cardiovascular death and fatal PE.

- All components are not equal, and patients are sure to prioritize cardiovascular death and fatal PE over asymptomatic DVT.

- Combining multiple endpoints into a single outcome increases the chance of masking more important patient-centered outcomes.

- The components did not occur at the same frequency, and asymptomatic VTE drove the outcome in this trial.

- Protocol Violations:

- Not all patients had definitive radiographic imaging described in the study design which introduces bias.

- This should be considered a loss to follow-up. Ideally, all patients lost to follow-up are assumed to have the endpoint, but the investigators didn’t treat the results in this manner.

- Trial investigators were unblinded to the patient’s treatment arm. They mention that a higher percentage of patients in the experimental group had diagnostic imaging, but this could have been done selectively.

- Investigators could have selectively scanned patients who were likely to be negative in the experimental group and scanned patients they presumed would be positive in the control group, thus biasing the results in favor of the experimental group.

Author’s Conclusions: “In patients at high risk discharged after hospitalization due to COVID-19, evidence suggests that thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg/day through 35 days improved clinical outcomes, reducing thrombotic events, compared with no post-discharge anticoagulation.”

Clinical Bottom Line:

This study contains interesting data that could contribute to the standard of practice when treating patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. However, use caution when applying the results of this study. Several problems raise concern, including the open-label design coupled with the high percentage of protocol violations, as not every patient received diagnostic imaging. These issues introduce bias and limit the generalizability of the results.

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- REBEL EM: The ACTIV-4b Trial: Antithrombotics For Treatment of Outpatient COVID-19

- REBEL EM: The HEP-COVID Trial: Therapeutic Anticoagulation in Non-Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients

- REBEL EM: COVID-19 and Anticoagulation: Full Dose or Prophylactic Dose?

- Critical Care Reviews: mpRCT Anticoagulation Trial

- St. Emlyn’s Blog: Thromboprophylaxis for the Non ICU Hospitalised COVID-19 Patient

Guest Post By:

Jessica DiPeri, MD

PGY-2, Emergency Medicine Resident

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Email: jtilzer12@gmail.com

Marco Propersi, DO FAAEM

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @marco_propersi

Steven Hochman, MD FACEP

Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @hochmast

References:

- Al-Samkari, Hanny et al. “COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Blood vol. 136,4 (2020): 489-500. PMID: 32492712

- Connors, Jean M et al. “Effect of Antithrombotic Therapy on Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients With Clinically Stable Symptomatic COVID-19: The ACTIV-4B Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA 2021. PMID: 34633405

- Spyropoulos AC et al. Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic-Dose Heparin vs Standard Prophylactic or Intermediate-Dose Heparins for Thromboprophylaxis in High-risk Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: The HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2021. PMID: 34617959

- Spyropoulos, Alex C et al. “Predictive and associative models to identify hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE.” Chest 2011. PMID: 21436241

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)