This blog post first appeared on REBEL EM.

Background: Outside of early defibrillation and high-quality CPR, little has been shown to improve outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). In theory, rapid identification of the underlying cause of arrest can be beneficial. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been adopted into cardiac arrest care by many emergency clinicians for this reason.

Ultrasound is a rapid bedside tool that may help identify reversible causes, aid with procedural guidance and assess cardiac activity. (Gaspari 2016, Littmann 2014) Despite all these potential benefits, recent studies have expressed concern that utilizing ultrasound during rhythm checks may increase time spent off the chest. Prolonged pauses during CPR can portend worse outcomes for our cardiac arrest patients and we should focus on minimizing this time during resuscitations. In 2017, Clattenburg et al. showed that the use of POCUS lengthened this time by as much as six seconds. This is similar to another study that suggested an additional eight-second delay. (Huis in ’t Veld 2017) Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) recommends no more than 10 seconds during pulse checks. If we are to use POCUS to guide OHCA management, we must develop an approach that minimizes hands-off time.

Article: Romolo G et al. Echocardiographic Pre-pause Imaging and Identifying the Acoustic Window During CPR Reduces CPR Pause Time During ACLS – A Prospective Cohort Study. Resuscitation Plus 2021. PMID: 100094

Clinical Question: Is pre-pause imaging associated with a decrease in compression pause length and shorter image acquisition time?

Population:

Inclusion Criteria:

- All adult patients presenting following an atraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest actively undergoing CPR

Exclusion Criteria:

- Traumatic Arrest

- If resuscitation efforts were halted based on end-of-life care decisions

- Video recording was lost and not reviewable

- The clinician (supervising physician and/or resident) performing the echo was not credentialed

Intervention:

- Emergency medicine attendings/residents at UMASS Memorial Medical Center completed a 30-minute training and didactic session at the 6-month point of the study.

- Participants were taught to place the transducer on the subject’s skin during CPR to identify the optimal cardiac “window” where the heart is best visualized.

- After the training and for the last 7 months of the study, participants were encouraged to utilize pre-pause imaging during codes.

- When CPR was paused, the transducer was already in place and may only need micro-adjustments to obtain higher quality views.

Control:

- The First 6 months of the study was the baseline period which did not consist of pre-pause imaging nor education sessions.

Outcomes:

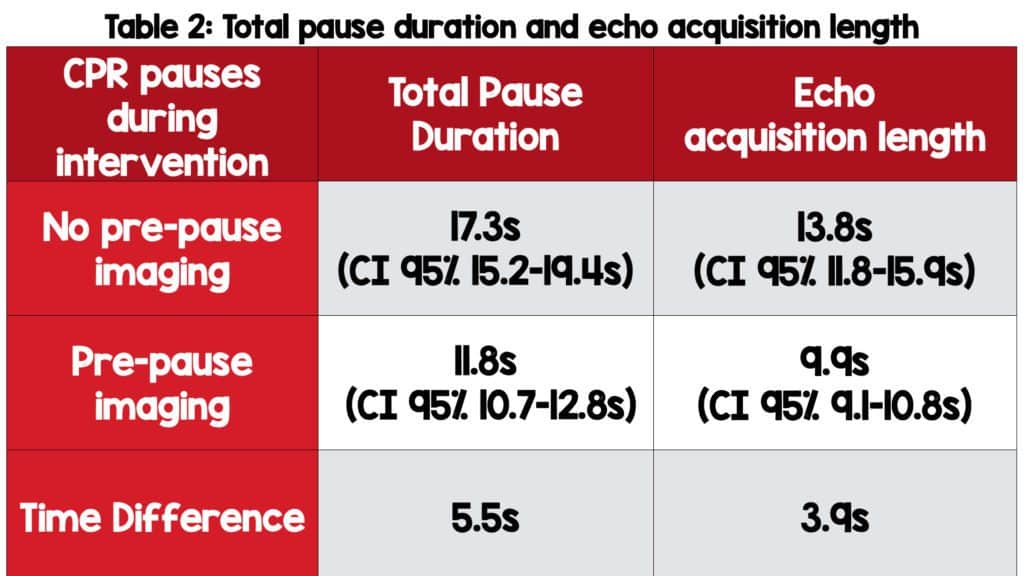

Primary: Change in length of CPR pause after integration of pre-pause imaging into ACLS

Secondary:

- Comparison of CPR pauses with and without echo

- Length of echo during pauses in CPR before and after integration of pre-pause imaging into ACLS

- Differences in image quality of echo images before and after integration of pre-pause imaging into ACLS

- Differences in survival before and after pre-pause imaging were included into ACLS

What They Did:

- Interventional cohort study with 6-month baseline period without formal training or didactic in cardiac ultrasound

- A 7-month interventional period in which residents/attending physicians involved in the study received formal cardiac ultrasound training.

- Emergency physicians completed a standardized 30-minute training session in cardiac ultrasound as stated above.

- Resuscitations were video-recorded

- Time of echo image acquisition is defined as the time from when the probe is placed on the chest to the time when taken off.

- Image quality graded on a 1-5 scale

- 1 – unable to interpret

- 2 – can only tell if the heart is beating

- 3 – sufficient to tell if organized vs. disorganized activity

- 4 – sufficient to visualize internal details of the heart (myometrium, valves, pathology)

- 5 – sufficient for quantitative analysis

Results:

- 162 patients identified

- 145 included in the study

- 17 patients were excluded because of the loss of video clips that were unable to be reviewed.

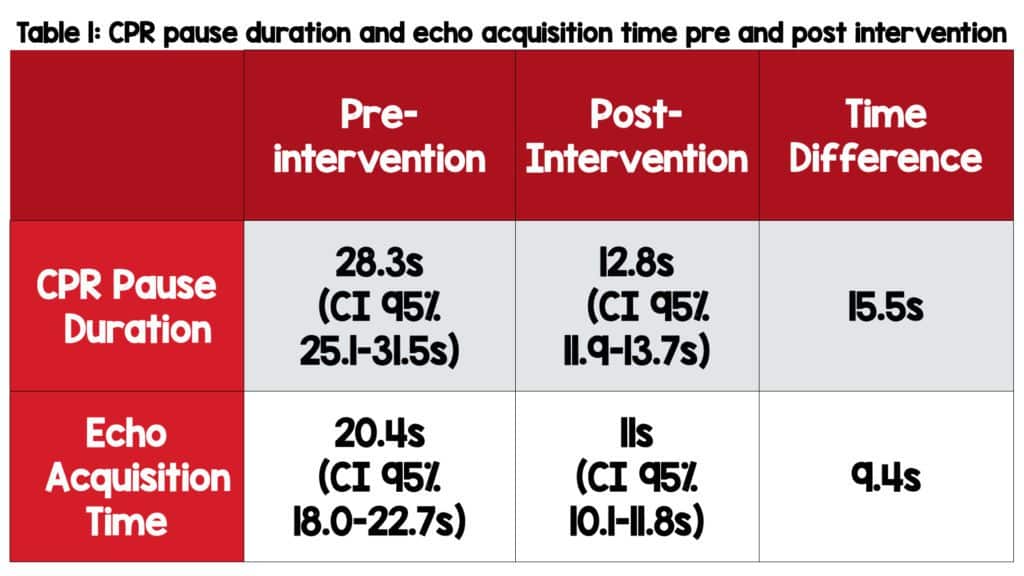

Critical Findings:

- CPR pause duration decreased by 15.5 seconds from the pre and post-intervention period (primary outcome)

- Echo acquisition time decreased by 9.4 seconds

- Image quality remained consistent (3 vs. 2.7 with a 0.68 kappa agreement)

Strengths:

- A prospective study with consecutive enrollment reduces selection bias

- CPR resuscitations were filmed and analyzed with defined start and stop parameters

- Image analysts had a defined image quality scale

- Image analysts had a similar experience level in reading cardiac ultrasound

- Multivariate analysis was performed for each individual pausing event decreasing confounding factors that could have increased CPR pause time not related to ultrasound or pre-pause imaging

Limitations:

- The primary outcome is not patient-oriented—the patient doesn’t care how long their pause was but whether they had a good outcome.

- Important to know if the ultrasound info changed anything—gave a diagnosis, made them change the way they do compressions, etc.

- That being said, we know longer pauses are bad so, we are using this as a surrogate marker

- Not a completely blinded study as only the image analysts and data analysts were blinded to outcomes.

- The study was performed at an ACGME-approved emergency medicine residency and ultrasound fellowship program and therefore these results may not be generalizable to places in a non-academic setting with less POCUS experience.

- Hawthorne effect: The residents and attendings knew there was a study.

- They may have worked harder to get on and off the chest faster.

- There was additional training that may have improved the skills of clinicians. With before and after, simply the overall skill set of the clinicians could have improved.

Discussion:

- This study adds to the literature about the use of ultrasound during cardiac arrest and suggests a potential intervention to decrease CPR pause length.

- It’s critical to note that pauses were 28.3 seconds at baseline prior to training. That’s nearly three times the ALCS recommendation of 10 seconds.

- It may be easy to show improvement when your baseline is so bad.

- Even with the addition of training with ultrasound and pre-pause imaging participants still do not get under the 10-second recommendation.

- Another major downside is the lack of blinding of the clinicians performing the ultrasound. It is impossible to say whether the pre-pause imaging resulted in the shorter pulse check times or just the overall awareness of time secondary to the educational intervention.

- How can we decrease pulse check times to the recommended 10 seconds in the ACLS guidelines? It’s likely multifactorial. Although not evidence-based, experts in the field have suggested several interventions, in addition to pre-pause imaging::

- Consider recording a video clip and analyzing/interpreting once the resuscitation has completed

- Have a timer and continue compressions at the 10-second mark even with inadequate cardiac views

- Have the most experienced person perform the ultrasound (this should not be the team leader of the resuscitation)

- Use of an ultrasound protocol; the Cardiac Arrest Sonographic Assessment (CASA) exam is one such example. (Gardner 2018) [Link is here]

- Use of Transesophageal Echo (TEE)

Author’s Conclusions: “Pre-pause imaging was associated with significant decrease in CPR pause length and US image acquisition time. Further research is needed to better define image acquisition techniques during cardiac arrest, but pre-pause imaging may help to better integrate ultrasound into ACLS.”

Our Conclusions: Pre-pause imaging has the potential to decrease time spent in pulse checks. However, based on this study, it is hard to say whether this alone was the reason versus the overall educational intervention provided to emergency providers. Nevertheless, this study strengthens the idea that being cognizant of CPR pause length and enforcing simple steps to keep time as close to 10 seconds has the potential to provide better care for our patients.

Clinical Bottom line:

Pre-pause imaging is one of many tools with the potential to decrease pause length during CPR. Though the study is not without flaws, we see little downside to adopting pre-pause imaging and highly recommend its use during cardiac arrest. However, we still need more evidence to improve and refine our management during cardiac arrest, particularly with an eye at pause times. Finally, ED physicians should continue to use POCUS to help diagnose, manage, and prognosticate patients presenting in cardiac arrest.

References:

- Gaspari R, Weekes A, Adhikari S, et al. Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016. PMID: 27693280. [Link is here]

- Littmann L, Bustin DJ, Haley MW. A simplified and structured teaching tool for the evaluation and management of pulseless electrical activity. Med Princ Pract. 2014. PMID: 23949188. [Link is here]

- Clattenburg EJ, Wroe P, Brown S, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound use in patients with cardiac arrest is associated with prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation pauses: A prospective cohort study. Resuscitation. 2018. PMID: 29175356. [Link is here]

- Huis in ’t Veld MA, Allison MG, Bostick DS, et al. Ultrasound use during cardiopulmonary resuscitation is associated with delays in chest compressions. Resuscitation. 2017. PMID: 28754527. [Link is here]

- Gardner KF, Clattenburg EJ, Wroe P, et al. The Cardiac Arrest Sonographic Assessment (CASA) exam – A standardized approach to the use of ultrasound in PEA. Am J Emerg Med. 2018. PMID: 28851499. [Link is here]

Guest Post By:

Abdo Zeinoun, MD

PGY-1, Emergency Medicine Resident

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Email: abdo.szeinoun@gmail.com

Nicole Yuzuk, DO

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Email: yuzukn@sjhmc.org

Marco Propersi, DO FAAEM

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @marco_propersi

Steven Hochman, MD FACEP

Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson New Jersey

Twitter: @hochmast

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)