Written by Amanda Russo, DO

This post first appeared on REBEL EM [Link is here]

Background: Race is a sociological construct that affects how clinicians deliver health care to various racial/ethnic groups. This in turn affects clinical outcomes. Thus, African Americans with chronic kidney disease have worse outcomes with respect to hypertension control, timely nephrology referral, dialysis fistula/graft placement, adequate dialysis treatment, and access to transplantation. The precise reason for this difference is unclear but one proposed cause is the race multiplier term in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) equations.

The MDRD and CKD-EPI studies developed the equations most commonly used for eGFR in hospitals today. This article aims to illuminate how the race multiplier in the eGFR equations impacts care for African Americans with chronic kidney disease.

Clinical Question: What is the impact of the race multiplier for African-Americans in the CKD-EPI eGFR equation on CKD classification and healthcare delivery?

Paper: Ahmed S et al. Examining the Potential Impact of Race Multiplier Utilization in Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Calculation on African-American Care Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):464-471. PMID: 33063202

What they did:

- Cross-sectional study

- Analyzed 56,845 patients in the Partners HealthCare System Chronic Kidney Disease (PHS-CKD) Registry

- Included two large academic medical centers and affiliated community primary care and specialty practices in Boston, MA during 2019

- 2,225 (3.9%) identified as African American

- Investigators removed the race multiplier on the eGFR equation and compared the resulting clinical data and eligibility for referral, evaluation, or waitlist for a kidney transplant and dialysis access placement.

Inclusions:

- All patients in the CKD registry were evaluated for potential inclusion

- Inclusion in the registry requires a diagnosis of CKD, and patients must meet one of the following:

- Most recent eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and one additional eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at least 90 days prior

- At least two values of urine total protein or urine albumin > 300 mg/g

- ESRD or dialysis on problem list or as an International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code.

Exclusions:

- History of kidney transplant

- < 21 years old or >100 years

- Previously received dialysis

Intervention:

- Removal of race multiplier in the CKD-EPI eGFR equation

Outcomes

- Effect of race multiplier on referral, evaluation, or waitlist for a kidney transplant.

- Effect of race multiplier on dialysis access placement.

Results:

- Comparison of demographics

- 2,225/56,845 of patients identified as African American

- 16.7% of African Americans had advanced CKD (stage 4 or 5) compared to Whites at 10.8%

- The proportion of patients with hypertension was 88.1% in African Americans, the second-highest amongst all racial groups.

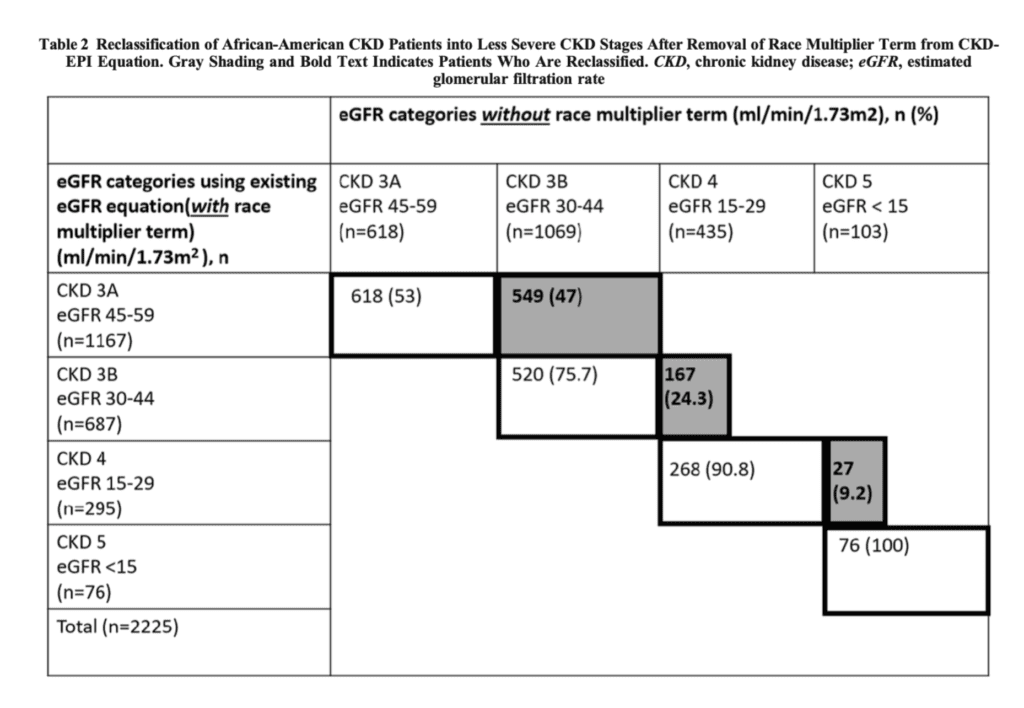

- Evaluation and reclassification of CKD stage with race multipliers removed

- 434 African Americans would be reclassified to early-stage CKD, increasing the total number of African Americans with CKD from 2,225 to 2659 — a 19.5% increase.

- Of 2,225 African Americans, 743 (33.4%) would move to a more severe stage of CKD, as seen in Table 2 below

- Effect of race multiplier on referral, evaluation or waitlist for a kidney transplant.

- 64/2069 African American patients would be reclassified from eGFR >20 ml/min/1.73m2 to eGFR < 20 ml/min/1.73m2. None of these patients had transplant referrals.

- Effect of race multiplier on dialysis access placement.

- No significant differences were found when the race multiplier was removed, with respect to dialysis access placement.

Strengths:

- Data were obtained from a large institution with academic and community practices, allowing for a large population of patients with CKD.

- Researchers obtained input from both nephrologists and health equity experts. This allows them to obtain various ideas from experts in both fields.

Limitations:

- Small percentage of African American patients in the cohort (only 3.9%)

- This study only evaluated the care within one healthcare system; it is possible that patients received part of their care outside of this system

- Patients, even though reclassified by the race multiplier, could have obtained dialysis referral or kidney transplant management at another facility

- Hypothesis generating – Findings suggest an association, but not causation

Discussion:

- Eliminating the race multiplier can have a tremendous impact on healthcare

- Reclassified about one-third of African-Americans to a more severe stage of CKD

- Demonstrated reclassification and how it influences the number of African-American patients who received adequate healthcare such as transplant referral

- The CKD-EPI equation utilizes race as a biological variable when it is a social construct

- This brings awareness to racial disparities in healthcare and brings this to light for healthcare providers

- Cross-sectional study

- An observational study that analyzes data from a population at a specific point in time.

- Used to assess the prevalence of a disease.

- They often involve secondary analysis of data collected for another purpose.

- The findings suggest an association, but not causation between the eGFR multiplier and direct patient care.

- There could be other confounding factors that affect the data that are not addressed.

Authors’ Conclusions: “Racial disparities in CKD have been well described and continue to exist. It is important to consider that widespread, unexamined use of the race-adjusted eGFR equation may perpetuate and/or exacerbate these inequities but does not fully explain racial inequities, and CKD-specific health equity efforts are needed. Based on our findings, racial correction in eGFR can potentially impact care for African-American patients with advanced CKD. Considering the evidence of this unfavorable impact on care delivery for African-Americans, use of the eGFR race correction factor needs to be reconsidered and, at a minimum, providers should be transparent about its use.”

BOTTOM LINE:

The use of eGFR equations with race multipliers may overestimate the GFR of African-American patients with CKD, thereby denying them access to appropriate care and perpetuating healthcare inequities.

Guest Post By:

Amanda Russo, DO

PGY-2, Emergency Medicine Resident

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, New Jersey

Email: adrusso91@gmail.com

Marco Propersi, DO FAAEM

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, New Jersey

Twitter: @marco_propersi

Steven Hochman, MD FACEP

Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine

Saint Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, New Jersey

Twitter: @hochmast

References:

- Coates T. What We Mean When We Say ‘Race Is a Social Construct’. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/05/what-we-mean-when-we-say-race-is-a-social-construct/275872/. Published May 15, 2013.

- Ahmed S, Nutt CT, Eneanya ND, et al. Examining the Potential Impact of Race Multiplier Utilization in Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Calculation on African-American Care Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):464-471. PMID 33063202

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2008 Oct 7;149(7):519] [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2021 Apr;174(4):584]. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. PMID: 16908915

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461-470. PMID: 10075613

- Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458. Published 2016 Dec 8. PMID: 27932337

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)